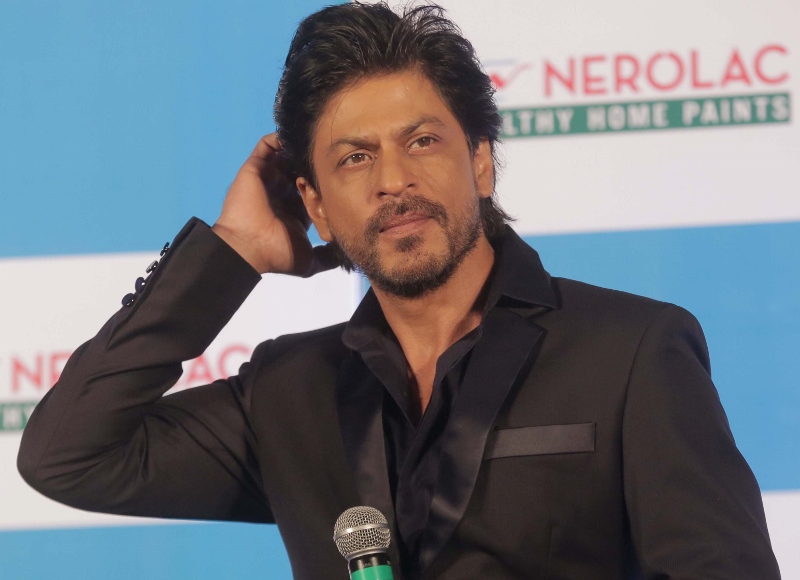

Protests have broken out in northeast India over Narendra Modi’s contentious new citizenship law, which makes naturalisation for Muslims harder.

India’s major step toward the official marginalisation of Muslims approved by one house of Parliament saw the passing of a bill that would establish a religious test for migrants who want to become citizens.

Solidifying Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist agenda, the bill makes religion a criterion for nationality for the first time.

The measure would give migrants of all of South Asia’s major religions a clear path to Indian citizenship – except Islam.

It is the most significant move yet to profoundly alter India’s secular nature enshrined by its founding leaders when the country gained independence in 1947.

The bill passed in the lower house, the Lok Sabha, on Wednesday 11th December, with a vote of 311 to 80.

The measure now moves to the upper house, the Rajya Sabha, where Mr Modi seems to have enough allies that most analysts predict it will soon become law.

But opponents say the law is discriminatory and violates India’s constitution and the country’s Muslims are deeply unsettled.

They see the new measure, called the Citizenship Amendment Bill, as the first step by the governing party to make second-class citizens of India’s 200 million Muslims, one of the largest Muslim populations in the world, and render many of them stateless.

The legislation goes hand in hand with a contentious program that began in the northeastern state of Assam this year, in which all 33 million residents of the state had to prove, with documentary evidence, that they or their ancestors were Indian citizens.

Approximately two million people – many of them Muslims, and many of them lifelong residents of India – were left off the state’s citizenship rolls after that exercise.

Now, Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is hoping to expand that kind of citizenship test to other states. And the new legislation would become a guiding principle for who could hope to call themselves Indians.

Mr Modi and his party are deeply rooted in an ideology that sees India as a Hindu nation. And since the B.J.P.’s landslide re-election win in May, Mr Modi’s administration has celebrated one Hindu nationalist victory after another.

First came the Assam citizenship tests. Then Mr Modi stripped away autonomy and statehood for Kashmir, which used to be India’s only Muslim-majority state. And last month, Hindu fundamentalists scored a big court victory allowing them to build a new temple over the ruins of a demolished mosque in the flashpoint city of Ayodhya.

With the new citizenship bill, Mr Modi’s party says it is simply trying to protect persecuted Hindus, Buddhists and Christians (and members of a few smaller religions) who migrate from predominantly Muslim countries such as Pakistan or Afghanistan.

But the legislation would also make it easier to incarcerate and deport Muslim residents, even those whose families have been in India for generations if they cannot produce proof of citizenship.

Under Mr Modi’s leadership, anti-Muslim sentiment has become blatantly more mainstream and public. Intimidation and attacks against Muslim communities have increased in recent years.

Mr Modi’s fellow lawmakers in the BJP are unapologetic about their pro-Hindu position.

The leaders of the opposition – the Indian National Congress party, paint the bill as a danger to India’s democracy.

After India won its independence, its founding leaders, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru among them, made a clear decision: Even though the country was 80 per cent Hindu, it would not be an officially Hindu nation. Minorities, especially Muslims, would be treated equally.

But the Congress party is at a low point in its 100-year-plus history. And Mr Modi’s party has the numbers: With allies, it controls nearly two-thirds of the seats in the lower house.

Some of Mr Modi’s critics believe the bill is serving to distract the public from another pressing issue: the economy. For the first time in decades, India’s economy is slowing significantly. It is still huge, but several big industries, like car and motorcycle manufacturing, have seen sales plummet like never before.

But forging India into an overtly Hindu nation has been a core goal of Mr Modi’s party and of the R.S.S., a right-wing volunteer group whose ranks Mr Modi rose through and which provides him with a backbone of support. His recent moves in Kashmir, along with the Ayodhya temple ruling and the Assam citizenship tests, have been hugely popular with the prime minister’s base.

Mr Shah, the home minister and architect of the B.J.P.’s recent political victories, promised to protect the Hindus and other non-Muslims. He has called illegal migrants from Bangladesh “termites,” and along with his other statements made clear that Muslims were his target.

The citizenship bill is a piece of the campaign to identify and deport Muslims who have been living in India for years, critics of the bill say.

Her Shah has promised to impose the citizenship test from Assam on the entire country.

Mr Modi’s supporters employ a certain logic when defending the bill’s exclusion of Muslims.

They say that when India and Pakistan were granted independence in 1947, the British carved out Pakistan as a haven for Muslims, while India remained predominantly Hindu. To them, the extension of that process is to ask illegal Muslims migrants to leave India and seek refuge in neighbouring, mainly Muslim nations.