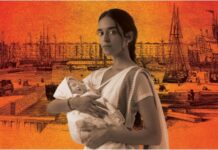

The Empress, written by Tanika Gupta, is set in 1887, the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, and tells the story of the sixteen-year-old Rani Das, ayah (nursemaid) to an English family, who arrives at Tilbury docks after a long voyage from India, to start a new life in Britain. On the boat, Rani befriends a lascar (sailor), an Indian politician and a royal servant destined to serve the Queen. Full of hopes and dreams of what lies ahead, they each embark on an extraordinary journey.

Spanning a period of 13 years over the ‘Golden Era’ of Empire, this epic drama takes audiences from the rugged gangways of Tilbury docks to the grandeur of Queen Victoria’s Palace, whilst unveiling the long and embedded culture of British-Asian history which continues to shape our society today.

Ahead of the show’s opening at The Swan Theatre, Stratford Upon-Avon, we spoke to Tanika Gupta about the inspiration behind The Empress, a play that reveals the often-overlooked experiences of British-Asians in Victorian Britain.

Q. What do you think led you to write The Empress?

The Empress for me, was a coming together of my interest in history, my parents’ story of immigration, the British Empire and the people who came here not just to make a better life for themselves, but from whose work we have gained so much.

In my early twenties, I read a wonderful book by Rozina Vishram ‘Ayahs, Lascars and Princes, Indians in Britain 1700-1947’. I was fascinated by the book, the stories and photos within it and the alternative history of Indian immigration.

Visram’s book had it all – but it was a history I had never read before, not even as a History undergraduate. As she writes in her introduction:

“It is often forgotten that Britain had an Indian community long before the second world war, and that the recent arrival of Asian people in Britain is part of the long history of contact between India and Britain. The arrival of Asians in Britain has taken place precisely because of these long-established connections.”

My initial inspiration came from an old black and white photograph taken in an ayah’s home in Aldgate in the 19th century. The picture of a group of Asian women sat around a table sewing and reading, wearing saris and Victorian dress, intrigued me. What were these women all doing in East London at the turn of the last century?

The picture and the stories in Visram’s book haunted me for many years until one day I told the then Artistic Director at the RSC, Michael Boyd, that I wanted to write a play about British Asians in nineteenth century London. He was up for it and happily commissioned me.

Q. The play begins in 1887, the year Queen Victoria celebrates her Golden Jubilee, and, for the first time, we meet our five main characters on a ship approaching Victorian London. How can the stories of these characters in The Empress relate to modern audiences?

“The contrast between the powerful and the powerless in Victorian London was dramatic, but Indians were to be found everywhere – from the East End docks to the Palace of Westminster, from the Hackney streets to the private rooms of Queen Victoria. This is an unknown history that has been silenced for too long.”

The experiences of immigration are echoed through the years and some of the characters in The Empress could almost be contemporary ones.

Immigration is a controversial political topic in our own time and many of today’s issues and debates are the same as those in the past. At this very moment refugees arrive in boats, desperately trying to escape starvation, poverty, war and climate change; impoverished, homeless people are destitute on the city streets, racism and prejudice continues, but through it all, the indomitable spirit of people like Rani persists.

Q. You’re a second generation immigrant, and a descendent of the Indian revolutionary Dinesh Gupta (who fought against British rule in India). Do you think your own family’s experiences have motivated your interest in British colonial history?

My own parents travelled to the United Kingdom from the city of Calcutta in recently independent India (1947) in 1961 in their early twenties and myself and my younger brother were both born here. My parents thought they were coming to the golden world of Shelly, Keats, Byron and of course Shakespeare, but the reality was a lot harsher to begin with.

They were graduates from university and spoke English well but struggled for years facing poverty, racism, bad housing and exclusion from employment. They were proud Bengalis, who believed fiercely in giving their children a good education and my father in particular was a brilliant storyteller.

I grew up hearing the stories of the epic Mahabharata, Ramayana, the history of India and the struggle from independence from British colonial rule, which his family were closely connected to.

Through my father’s stories of the injustice of the British Raj in India, through the years, I also became very interested to learn more about British colonialism. It is a fact that at its height the British Empire was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By 1920, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, and covered 24 percent of the Earth’s total land area.

Q. Rani, played by Tanya Katyal, is an Ayah. What was an Ayah?

Ayahs were Indian nannies who worked for English colonial families in India. They were more than babysitters – they were almost alternative mothers – spending most of their time caring for the children, and their wages were an eighth of the wages of an English nanny.

By the 1850s, as travel became more regular, the number of Ayahs brought to Britain increased. Between 100 and 140 travelling Ayahs visited Britain every year but once in Britain, many Ayahs were dismissed without pay. They usually had no formal contract of employment and return passages agreed in India were not always honored. While awaiting employment with a family going to India, the Ayahs stayed in squalid lodging houses that charged high rent.

An 1855 report drawing attention to their situation mentioned 50-60 Ayahs living together in a disreputable lodging house on Ratcliffe Highway in the East End of London. Some Ayahs were forced to beg in the streets for a passage back home. Hence the Ayahs Home in Hackney was set up when Christian charities became concerned for the welfare of the abandoned Ayahs. The home provided accommodation for both Indian Ayahs and Chinese Amahs (who did a similar job to Ayahs). Established first in 1891 at 6 Jewry Street, Aldgate, East London, the Home was taken over by the London City Mission, who moved it to 26 Edward Road, Mare Street, in Hackney, East London in 1900. In 1921, the Home was relocated to bigger premises at 4 King Edward Road and thousands of Ayahs went through it right up until 1947.

Q. Hari, played by Aaron Gill, is a Lascar. What was a Lascar?

Lascars first began to be employed in small numbers from the seventeenth century by the East India Company, which was set up by private merchants in 1600 by Royal Charter to establish trade links with India. The term ‘Lascar’ became a term for almost all non-European sailors. Shipping companies recruited men of many backgrounds, including Arab, Cypriot, Chinese and East African but the majority were recruited from the Indian subcontinent, mainly from coastal areas of Gujarat and Malabar on the west coast of India and the east coast from the area now known as Bangladesh.

Once in Britain Lascars had to wait, sometimes for months at a time during winter before they could get a return ship back to India. Shipping companies did not provide proper accommodation while they waited, and in the nineteenth century, distressed Lascars were often seen wandering the streets. The term ‘the black poor’ was first used to describe destitute Indian sailors waiting to go home.

Christian missionary societies became concerned about the plight of Lascars and this led to the establishment of the ‘Strangers’ Home for Asiatics’, Africans and South Sea Islanders in West India Dock Road in the East End of London in 1856, which housed diverse groups of sailors.

Gradually, a small population of Lascars started to grow in London, Liverpool, Cardiff and Glasgow, forming the earliest Indian working-class communities in Britain. These port cities became multiracial settlements with sailors from diverse countries mixing relatively freely with the local population, some marrying and starting families with English and Irish working-class women.

Q. The Empress features a handful of real-life historical characters, can you tell us a bit about some of them?

There’s Abdul Karim, gifted to Queen Victoria (by the Viceroy of India) to celebrate her Golden Jubilee in 1887. Karim began his work in the Royal household as a waiter standing behind the Queen as she ate her breakfast but soon became the Queen’s close friend and confidante. He taught her Urdu and rose quickly in the ranks to become her munshi (Arabic teacher). Karim served Queen Victoria during the final fourteen years of her reign, gaining her maternal affection over that time, much to the consternation of the Royal Court and particularly the Queen’s son and heir – Edward – who despised him.

And there was Dadabhai Naoroji, the first ever Indian MP, elected in 1892 in Gladstone’s Liberal government. Naoroji also mentored British-Indian law students such as a teenage Mohandas Gandhi (later the Mahatma) and Mohammed Ali Jinnah (later the first Prime Minister of Pakistan). Naoroji had a huge influence on the politics of Gandhi and Jinnah. His economic critique of British rule in India, “the drain of wealth theory”, proposed that India was impoverished by British imperialism. The politics of Victorian Britain have always fascinated me but until I researched this play, I never appreciated quite how important London was for the emergence of Indian nationalism.

Also, Lascar Sally is a real historical figure who ran a boarding house near the London docks for Indian Lascars. It is said that she could speak fluent Hindi.

While there was a cast of remarkable and influential characters in London in the 1890s, I resisted their desire to dominate my play. I had to hold back on Queen Victoria and even on Gandhi, while allowing the voices of ayahs and lascars compete for centre stage. The contrast between the powerful and the powerless in Victorian London was dramatic, but Indians were to be found everywhere – from the East End docks to the Palace of Westminster, from the Hackney streets to the private rooms of Queen Victoria. This is an unknown history that has been silenced for too long.

Q. In 2019, The Empress was one of the texts chosen for the pilot scheme of Lit in Colour: Penguin’s campaign to increase the number of texts by Black, Asian and minority ethnic writers studied in schools. In 2019, fewer than 1% of GCSE English Literature pupils studied a book by a person of colour. Following a successful campaign, including participation from the RSC’s Youth Advisory Board, The Empress has been added to the GSCE Edexcel syllabus and the GCSE AQA Drama syllabus. What made you want to be a part if this campaign?

To me, this is part of a broader move to try and decolonise the curriculum. I have grown-up children now and even when they went through school, there was nothing for them in terms of their own culture.

But it’s not just about Asians learning about Asians, and Africans learning about Africans. It’s about everybody learning about each other’s history through literature. Without that, nothing’s going to change. It all starts with education.

Q. The Empress first premiered at The Royal Shakespeare Company a decade ago in 2013. Ten years on, do you feel much has changed in terms of Britain’s understanding of its own past?

I do think that the effects of British colonialism in India have been under much scrutiny over the last decade. Writers and thinkers such as Sathnam Sanghera, Amartya Sen, William Dalyrymple Shashi Tharoor and Arundhati Roy (to name but a few) have written extensively on the subject – questioning to the hitherto Eurocentric view on this period of history. I still think there’s much more work to be done to educate our British school students on the subject – to really engage with a critique of Empire.

Unfortunately, the current British government’s obsession and war against immigrants means that positions have become even more entrenched and there seems to be a lack of knowledge, bordering on racism when it comes to this subject. ‘We are here, because you were there’ is one of my favourite ways of summing up the situation.

Q. What do you hope audiences will take away from watching this production of The Empress?

I hope audiences will be thoroughly entertained and engaged by The Empress. It has a cracking story at the heart of the play of a bright, young Indian woman arriving on the shores of Britain in 1887 and trying to make her way through a bewildering cold and alien society – making many friends and falling in love along the way. And of course, Queen Victoria and her relationship with her Indian man servant Abdul Karim is beautifully re-enacted. The play has new music composed for it by the Ringham Brothers, live musicians, dancing, a lot of humour, as well as tragedy.

This is Victorian Britain as you’ve never seen it before!

The Empress is running at Swan Theatre util Friday 15 September 2023 before transferring to the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre in London from Wednesday 4 October to Saturday 28 October. The production will then return to the Swan Theatre from Wednesday 1 November to Saturday 18 November 2023.